Latst News and Blog

The History of Borstals in England - Part 3 - Food

16/09/2024

Dan Ewers is a PhD researcher based at the University of Leeds. During 2023 he explored the archives held at the National Justice Museum researching the history of borstal institutions in the United Kingdom. Over the next few months we will be sharing what Dan found out about health, wellbeing, and everyday life within borstal institutions.

In this blog post, Dan’s research is exploring the history of food in borstal, before taking a closer look at what the boys at Gaynes Hall Borstal ate on a day-to-day basis.

Rochester Borstal Dining Hall, c.1910s.

Food formed a central element of life in borstals. One of the underlying principles of the early borstals was that the food provided had to be nourishing and plentiful, with the intention of building juveniles’ bodily health and physical strength. They usually ate four meals a day (listed as ‘Breakfast, Dinner, Tea and Supper’ in some sources). Juveniles were understood to require a high-calorie diet, especially those in open borstals living active, primarily outdoor lifestyles. One report in 1949 gave the calorific value of borstal diets as being as high as 4495 calories for boys and 4329 calories for girls, considerably higher than the recommended daily amounts for adults today!

Mealtimes often varied from location to location. In some borstals, food was served inside cells to be consumed alone. In others, the juveniles ate together in large dining halls, either together with staff and other juveniles across the whole institution or subdivided by a House system like that found in public schools. The 1932 edition of Manual of Cooking and Baking also outlined adjusted diets for those with religious dietary rules, such as in the Jewish, Hindu, and Muslim faiths, as well as the guidelines for providing adequate and well-balanced nutrition.

Alongside eating food, juveniles in borstal would often be trained in the kitchens under the supervision of staff members before undertaking a cookery examination. This was intended to provide the juveniles with qualifications and skills to enable them to find employment more easily once they were released back into civilian life. For example, boys at the Hollesley Bay Colony borstal were trained by kitchen staff, which would often result in them undertaking the certification offered by the Nautical Cookery Association.

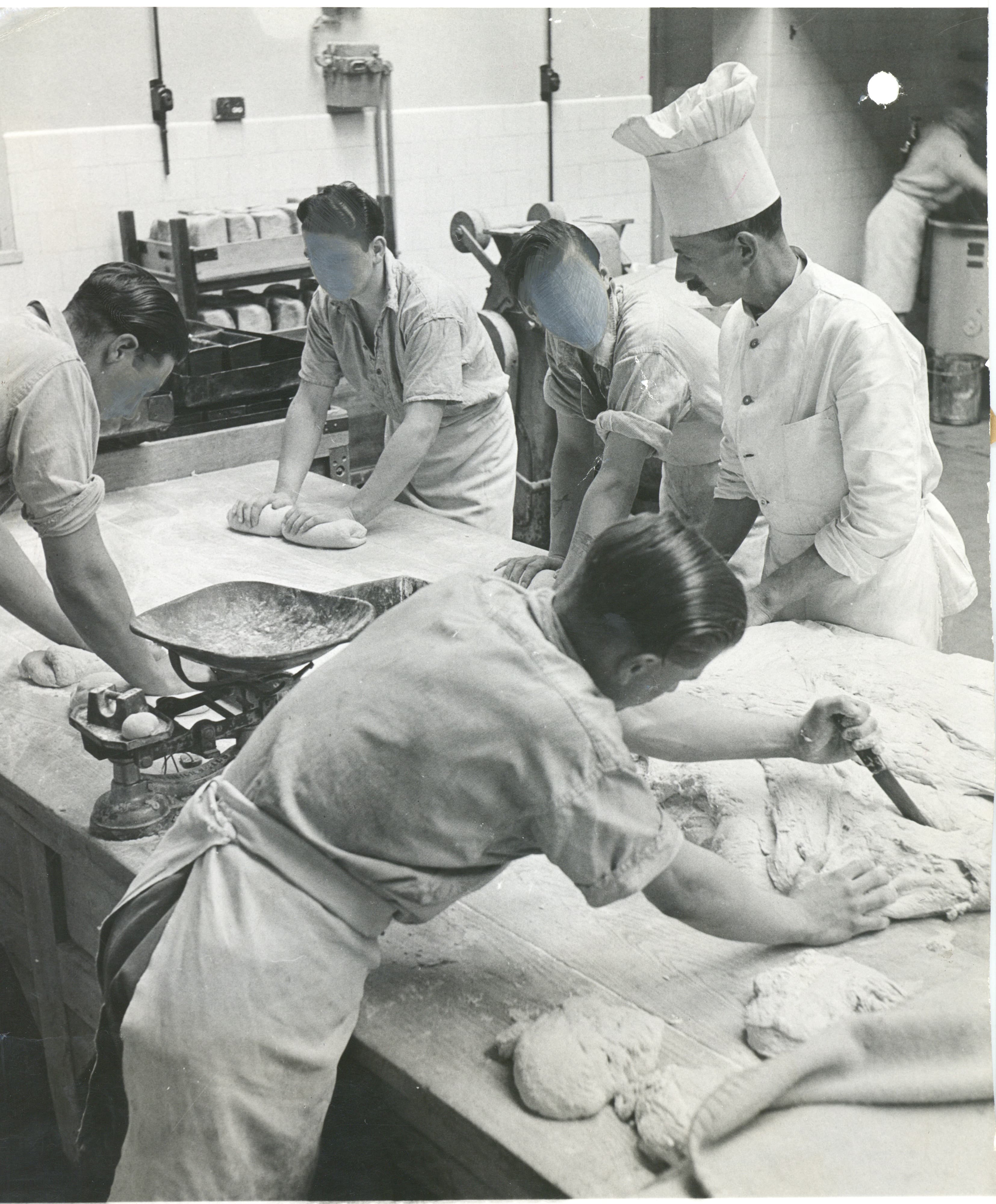

Borstal Boys Baking Bread at Feltham Borstal, c.1940s.

In the 1948-56 Visitor Books for Gaynes Hall Borstal, visitors regularly commented on the quality and quantity of the food served, with “100 well-made loaves baked under ideal conditions.” Preparing meals, baking bread, and assisting kitchen staff with food service all fell under the responsibilities of many juveniles in borstal as a core element of their training.

The Prison Service archive at the National Justice Museum contains three menu books from Gaynes Hall open borstal in Cambridgeshire. They outline what food was served on each day between 1975 and 1977. These menu books would be filled out weekly by the Cook and Baker Officer and subject to daily approval by the Governor and Medical Officer. Certain rules had to be followed, such as that similar dishes should not be served on the same day each week, or that the main and sweet dishes of a meal should provide a contrast to one another wherever possible.

So, what do these Menu Books reveal about what the borstal boys at Gaynes Hall ate?

A typical day at Gaynes Hall in the mid-1970s usually featured four meals, served at Breakfast, Lunch, Dinner, and Supper.

Breakfast usually contained a grain-based element, such as cereal or porridge, alongside a hot element such as grilled sausages, grilled bacon, eggs, and baked beans, as well as bread, margarine, and tea.

The midday meal was typically the largest meal of the day, with boys who were working on the grounds or offsite often being provided with a packed lunch. Common items on the menu included liver and onions, braised hearts, roast chicken, cheese & onion flan, and a steamed meat roll. On Sunday, the menu books show that the boys were almost always served a dinner of roast meat (typically beef) and mixed vegetables.

The evening meal also typically contained a substantial hot menu option, often accompanied by a side of vegetables. Items listed in the menu book included kippers, beefburgers, sausage rolls, cold luncheon meat, fried fish, and curry stew.

Supper was usually a sweet item, such as a slab cake, scone, or sweet bun, or a piece of fruit, usually an apple or a banana.

The Menu Books also shed light on the influence of different international cuisines on the food offered within Gaynes Hall’s dining room in the 1970s, with the appearance of spaghetti bolognaise, hamburgers, pizza, beef curry stew, cheese and ham souffles, and on one occasion a cheese fondue!

The Gaynes Hall Menu Books can also show us what Christmas dinner looked like for borstal boys! The meal served on Christmas Day 1975 consisted of the following:

Breakfast - Alpen, sausages, bacon, grapefruit, coffee (a rare item to find in the menu books – boys appear to have almost exclusively had tea!) bread, margarine and marmalade.

Lunchtime – A Christmas dinner consisting of soup, roast turkey, cranberry sauce, sage and onion stuffing, peas, mixed vegetables, roast potatoes, and gravy. For dessert, a serving of Christmas pudding with rum sauce.

Evening Meal - Christmas cake and tea was served alongside ‘Christmas Parcels’. These parcels were usually part of a scheme organised by Toc H which provided parcels donated by schools across the UK. They would be given to boys in borstals who were homeless or would (for whatever reason) be unlikely to receive a gift from their families at Christmastime, so that they would have something to open on Christmas Day.

For supper before bed, the boys were given sausage rolls, mince pies, and orange squash to drink.

Food in Young Offenders Institutions Today

In a 2016 report on food in prisons, the HM Inspectorate of Prisons reported that “although many establishments are making commendable efforts with the resources available, too often the quantity and quality of the food provided is insufficient and the conditions in which it is served and eaten undermine respect for prisoners’ dignity.” The report also highlighted that, in 2014-15, whilst the average daily spend per patient on food services in hospitals was £9.88, by contrast ‘the basic catering budget allowance per prisoner per day was previously £2.02’. The report also called for specific nutritional values and conditions under which food should be eaten to be regulated, as well as calling for more opportunities for communal eating.

Food regularly features in the reported testimonies of young people within the Youth Secure Estate, with hunger appearing as a recurring issue. The size of food portions, the high prevalence of salty and sugary items, and the limited provision of adequate fruit and vegetables within the menu has all been reported within various findings papers. One study by Jenny Chambers in 2011 even reported that fruit had become currency within one Young Offender Institution, owing to the scarcity of healthy options on offer.

Food was (and continues to be) an important part of life within the Youth Secure Estate. Nourishing and nutritional food, containing adequate levels of vitamins, macronutrients, and calories, is essential for the health and wellbeing of young people within institutional settings.

This research has been produced by as the result of a 4-month REP placement at the National Justice Museum. Many thanks go to The National Justice Museum and the White Rose College of the Arts and Humanities for their support throughout this project.

OTHER NEWS AND BLOGS

Interview with a volunteer - Paula

Asking For It, an award-winning exhibition challenging the culture of victim-blaming, opens at the National Justice Museum

National Justice Museum announce recipient of £1000 photography Creative Residency Prize

UK-first bronze sculpture makes history in Nottingham’s Broad Marsh Green Heart

The History of Borstals in England - Part 6 - Medical Care

UK-first bronze sculpture for Nottingham’s Broad Marsh Green Heart confirmed for early 2025

The History of Borstals in England - Part 5 - Education and Routine

The History of Borstals in England - Part 4 - Health

The History of Borstals in England - Part 3 - Food

Picture This: Hope - Blog by last year's residency winner, Francesca Hummler

The History of Borstals in England - Part 2 - Farming and Agriculture

The History of Borstals in England - Part 1 - Timeline

Find us on the Robin Hood Adventure Trail this summer

National Justice Museum announces judges for Picture This: Hope photography competition

National Justice Museum, Nottingham, appoints four new trustees to its board

National Justice Museum and City of Caves Win Tripadvisor® Travellers’ Choice® Award 2024

National Justice Museum celebrates the life of its patron Lord Judge

National Justice Museum and City of Caves Recognized as Tripadvisor® 2023 Travellers’ Choice® Award Winners

An iconic piece of LGBTQ+ history returns to public display at the National Justice Museum

National Justice Museum is awarded a £249,996 grant by The National Lottery Heritage Fund

Immersive, site-specific performances come to the National Justice Museum for one day only

National Justice Museum's Open Court podcast back for a second season

Family devastation brought closer to home in knife crime prevention workshops

National Justice Museum announce recipient of £1000 photography award

National Justice Museum recognised as one of England’s outstanding cultural organisations through Arts Council England’s National Portfolio

National Justice Museum’s new open-call photography exhibition, Freedom, to open in November

The National Justice Museum explores untold stories of Black presence

National Justice Museum opens call out for object donations from Black Legal Professionals

National Justice Museum announces judges for Freedom photography competition

National Justice Museum Wins 2022 Tripadvisor Travellers’ Choice Award

Rolls Building Art and Education Trust & The Technology and Construction Court Art Competition

National Justice Museum opens submissions for photography exhibition with a £1,000 prize at stake

National Justice Museum to receive £362,900 in fund which helps safeguard nation's cultural heritage

The National Justice Museum publishes Letters of Constraint

National Justice Museum wins Best Museums Change Lives Project at Museums Change Lives Awards 2021

Welcome back S.H.E.D!

‘Freed Soul’ letters

Justice week 2021

Ghost stories with Claire

Autism and me

Staying proud

Ultimate travel list

The ‘Bloody Code’?